How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Revived Modern Myth-Telling

Stories of the famous writers of Oxford

In this nearly magical room, amid fire-crackle and clink of glass, you can hear them talking. Pipe smoke is in the air, and a certain boisterous chauvinism, and the wet-dog smell of recently rained-on tweed. You can hear the donnish mumbles of J. R. R. Tolkien as the slow coils of The Silmarillion glint and shift in his back-brain. Now he’s reading aloud from an interminable marmalade-stained manuscript, and his fellow academic Hugo Dyson, prone on the couch, is heckling him: “Oh God, not another fucking elf!” You can hear the challenging train-conductor baritone of C. S. Lewis, familiar to millions from his wartime radio broadcasts; hear the unstoppable spiel of the writer/hierophant Charles Williams, with his twitchy limbs and angel-monkey face; hear the silver stream of ideas and argumentation that is the philosopher Owen Barfield. They are intellectually bent upon one another, these men, but flesh-and-blood is the thing: conviviality is, for them, a kind of passion. The chairs are deep; the fire glows gold and extra fiery in the grate. Lewis’s brother, Warnie, rosy with booze and fellow feeling, serves the drinks. And the walls drop away, and the scene extends itself backwards and forward in time…

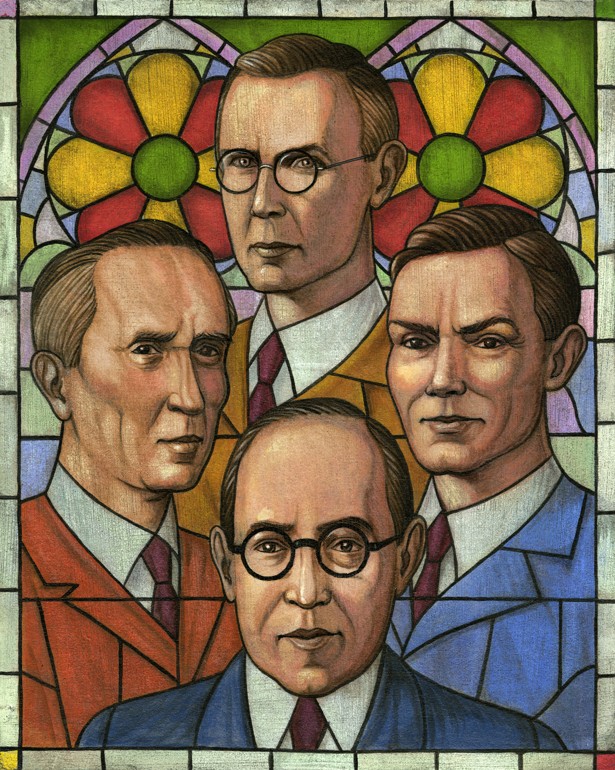

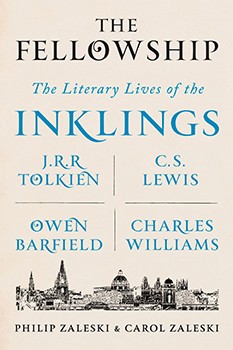

Philip and Carol Zaleski’s The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings is a mental map, a religious journey, and the biography of a brotherhood. Plenty of distinguished Inklings came and went over the years, padding across the carpets with a Warnie-provided drink in hand, but the Zaleskis zoom in on (and out from) the primary axis of Tolkien, Lewis, Williams, and Barfield, the four among whom the invisible correspondences of thought and affection were strongest. Christians all, these men formed what the Zaleskis call “a perfect compass rose of faith”: Barfield the proto–New Ager, Tolkien the rather prim orthodox Catholic, Lewis the noisy and dogmatically ordinary layman and popular theologian, Williams the ritualistic Anglican with a taste for sorcery.

“The qualifications … are a tendency to write, and Christianity.” Thus explained Lewis in a letter to Williams in March 1936, inviting him to a session of the “informal club” that had begun convening every Thursday night in his rooms at Oxford’s Magdalen College (and then again, still less formally, at the Eagle & Child pub on Tuesday mornings). The letter was a fan letter; the two men didn’t know each other, but Lewis had found himself compelled to inform Williams that reading his fantasy novel The Place of the Lion—in which comfy England is burst upon by unruly celestial essences—had been “one of the major literary events of my life.” Lewis was an Oxford fellow and tutor in English literature, and a relatively fresh-baked believer: after an arduous wrangle of a conversion, he had arrived at the knowledge of a personal God while sitting in Warnie’s sidecar on a motorcycle ride to Whipsnade Zoo. Williams worked in publishing, wrote feverishly, smoked like a chimney, delivered whirling literary-metaphysical lectures, and indulged in the overheated cultivation of female disciples. (One such pupil, we learn from the Zaleskis, was struck smartly on the bottom with a ruler.) Devoutly churchgoing, he was also of high rank in at least one esoteric mystical order and would make sacred signs while traveling on the London Underground. W. H. Auden thought him nearly a saint. To Lewis’s letter, Williams replied immediately that he had been on the verge of writing to Lewis, in praise of his The Allegory of Love. “It has never before happened to me to be admiring an author of a book while he at the same time was admiring me.” (Not a bad example of the loopy Williams prose style, that.) The serendipity, the crossbeams of appreciation, the ardent encounter at the aesthetic, soon to be spiritual, level—a very Inklings moment.

Fonte: http://buff.ly/2rp3u4H

EDUARDO

“Lewis, in particular, polemicized fruitily against materialism, atheism, 20th-century-man-ism. On the other hand, what more modernist project could there be than Tolkien’s “construction of an art-language,” with the obsessive completeness of its declensions and long-dead kings?”

Lewis fez um arte e foi um artista: ele conseguiu, e de certa forma enganou (do ponto de vista literário), que os mitos nórdicos fossem devidamente ‘reconstruídos’ e deles saíssem uma explicação quase que perfeita de como o Cristianismo poderia ser explicado (a moda de Lewis, claro), entendido e aceito. Os evangélicos americanos que nunca entenderam nem a mente e nem o contexto em que Lewis viveu e escreveu, produziram uma obra evangélica borrifada com docinho para o público, digamos, do baixo clero.

Tolkien foi, literariamente, mais honesto do que ele.

PS. Cheguei dos EUA semana passada com três livros sobre os mitos nórdicos, e um deles uma obra rara de como Lewis conseguiu ‘montar’, digamos, seu ‘esquema explicativo’.

Gabriele Greggersen

Olá Eduardo,

Desculpe decepcioná-lo, mas o autor está longe de dizer que a concepção virginal de Maria seja um mito. Pelo contrário, ela ultrapassa o mito, que não passa de um rascunho do fato. Ou seja, lamento lhe informar que não entendeu o ponto central do artigo.

E faço minhas as palavras de Lewis: “Aqueles que não acreditam que este grande mito se tornou fato quando a Virgem concebeu, merecem nossa compaixão.” Sugiro que você leia os textos desse site com um pouco mais de atenção e menos pré-julgamentos, pois esse tipo de leitura, sim, é que mostra falta de argumentos.